|

| Pink Cockatoo skin, photographed by Sara Porter |

Our bird skin collection has all been fully rehomed and documented. Now that the Skin Deep project has finished, the bird skins are all arranged in drawers, so are much more accessible to view and handle than their previous home in boxes.

Patterns and plumage - photographing the bird skin collection

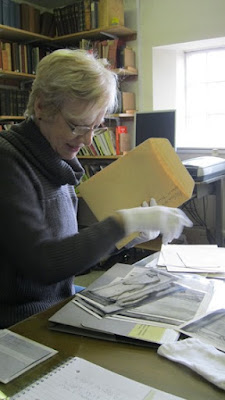

My work this morning was some of the nicest in a while! My task was to choose around a hundred bird skins to be photographed by Sara Porter for a new display panel in our Leeds Museum Discovery Centre store. I was looking for a range of colours and patterns, so all I had to do was take a peep in each drawer, picking out my favourite in each. I chose birds which covered all the colours of the rainbow, and more besides, as well as some which have amazing patterning on their plumage.I have seen the majority of our bird skin collection, but I was still taken aback by the beauty of these birds, as well as coming across some amazing specimens I hadn’t seen before. I really am privileged to be able to see the amazing plumage of these species close up. I thought to myself of the phrase ‘A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’. Obviously this is supposed to be a metaphor, but it got me thinking…

Why do museums preserve specimens?

One of the things that museums can offer visitors, researchers, and indeed staff like me, is the chance to see some of the immense biodiversity we share our planet with, up close. Seeing a specimen in a museum can be very useful to give a sense of size, and enables us to look closely at details we might miss when watching a living specimen in the wild. For instance, some of our butterfly collection have patterns which you would not be able to view closely if you saw a live butterfly flitting through a rainforest. |

| Speckled Tanager skin, photographed by Sara Porter |

Highlights of the collection

Taking the ‘bird in the hand’ adage literally, I couldn’t disagree with it more. It has been amazing looking closely at the plumage of beautiful (and beautifully named) birds such as Speckled Tanager, Splendid Sunbird and King Paradise Bird. But I would love to see a distant glimpse of any of these birds in their natural habitat. Imagine the sun reflecting off iridescent wings, or the movement of long tail plumes during flight. I can try to imagine, because I have seen these birds’ skins today. And that makes museums brilliant.Natural history collections offer us the chance to see some of the world’s biodiversity under one roof. But it would be a very sad world if all we could do were to imagine living birds from museum skin collections. Nothing can replace the experience of seeing nature, living, in the wild, complete with smells and sound and feeling.

By Rebecca Machin, Curator of Natural Sciences

Follow Rebecca on Twitter @Curator_Rebecca